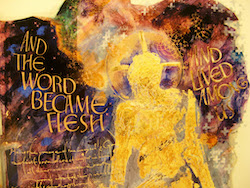

If faith and lectio divina are to mean anything together then it must be that lectio divina has the distinguishing characteristic of being incarnational. The Word has to take flesh again in us, and this is what we must aspire to when we approach Sacred Scripture – the whole of Scripture hinges and pivots around the Christ-event, either in preparation, or in actualisation, or in memorization, that’s to say, how it lives on in the memories of those who have experienced it (we might look at the First Letter of St John should we need any convincing of this in its effects).

And that memorization, the calling to mind which is memorial in its sacred and liturgical sense, and acknowledging our Jewish roots when we speak like this, is also a matter of faith: it inserts us into an event which is not closed as a single point in history but, because it is God’s intervention, and is salvific – after all it is the Word which creates, redeems, saves and restores all things – is an always present event, and we are part of it by our calling of it to mind.

This is why, I would suggest, it is so vitally important from the first monastic accounts of prayer and meditation with Sacred Scripture that the Word be committed to memory. Yes, of course, it is so in order that the Word may be called up again and again for us to chew and taste – but this is not merely a matter of a storehouse from which we bring forth things both old and new. Essentially it represents the vast field of memory, to use St Augustine’s language in Book X of The Confessions, from which we bring forth things which are present, since God’s remembering is always the present moment, into which all which might be called past and future is already poured and is present. Consider again how many times during the celebration of the Eucharist we are invited to “call to mind,” or we are reminded that we take part in a “memorial.” This means absolutely nothing to us if we cannot know that the Jewish roots of memorial immediately inform us that we are taking part in God’s once and for all, single, salvific intervention. Analogously we need to celebrate the reception of the Word of God, especially in our lectio divina, in precisely the same fashion.

We, if our lectio is framed in the right fashion and approached in the right way, aspire to enter into this present-moment-happening, which is participation in the divine salvific intervention.

It’s important here to reflect again on those words by which St Benedict instructs us in the right manner of our approach to the Opus Dei, or the Divine Office, in Chapter 19 of his Rule – Psallite sapienter, he tells us, and then goes on to caution that we should sing the psalms in such a way that “our minds are in harmony with our voices”. But this phrase means virtually nothing if we leave it blandly as “Sing wisely.” If we know that sapienter, wisely, has the same root as sapor, taste, then we make the connection with how we are to prepare to sing with wisdom.

We should be people who have already consumed, digested, tasted the Word of God, and who continue, in our prayer, to taste it again and again, and this extends into our tasting of the Word given us in our memory. Wisdom here is the reception by memory, and St Benedict insists on his monks memorizing the Word of Sacred Scripture.

While, of course, we should accept that the practical circumstances of Benedict’s day will have made this memorization a necessity – books, although probably more readily available in a monastery were hardly commonplace, and learning by rote was taken for granted, a practice which is coming back into vogue today – still, we have to accept that learning by heart, memorization, gave a flexibility and familiarity with text which could lead, almost inevitably, into the savouring of the saving, always present Word which continues to live within those who immerse themselves in it and is entirely assimilated by them.

Other posts…