We share with you a timely and insightful letter on prayer and hope from the Abbot General of our Order, Dom Bernardus Peeters ocso.

Circular Letter 26th January 2025

Brothers and sisters,

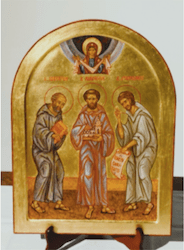

Midway through Advent, the Generalate received a beautiful gift of an icon of our Holy Founders, written by Sr. Suzanne Mattiuzzo of the community of the Redwoods (USA). The icon was painted on a board that came from the Ukrainian city of Kharkov, one of the many cities on earth where war and violence have caused so much devastation. Together with our Holy Founders, in the midst of this broken world, we live our Cistercian charism.

In this icon, we see our Holy Founders with St. Alberic in the middle, taking a step forward. He is approaching us, the spectators, as if to share with us the charism he has received. It begs the question, what are we doing with this gift in our own time?

What is this gift which our Holy Founders have given us? Constitution 2 defines the nature and purpose of our Cistercian life as follows:

This Order is a monastic institute wholly ordered to contemplation. The monks/nuns dedicate themselves to the worship of God in a hidden life within the monastery under the Rule of St Benedict. They lead a monastic way of life in solitude and silence, in assiduous prayer and joyful penitence as defined in these Constitutions, thus rendering to the divine majesty a service that is at once humble and noble.

At the beginning of this Jubilee Year 2025, dedicated to hope, which is also the year in which we will celebrate our General Chapter on the same theme, I would like to use this circular letter to draw attention to the essence of our Cistercian charism: “assiduous prayer” or “unceasing prayer.” There are three major expressions of prayer: vocal (liturgy), meditative (lectio divina), and contemplative, and they all have “one basic trait in common: composure of heart. This vigilance in keeping the Word and dwelling in the presence of God makes these three expressions intense times in the life of prayer.”

Our task as monks and nuns in this world is to bring hope to the world through our prayer. Pope Benedict XVI wrote in his encyclical Spe Salvi (2007): “A first essential setting for learning hope is prayer.” Over time, the Magisterium of the Church has often called on contemplative monasteries to be “schools of prayer.”

In addition to the fact that hope is the theme of the Jubilee Year 2025, as well as the theme of the General Chapter, I have another reason for bringing the theme of prayer to your attention. A survey on formation was recently sent to all the communities of the Order, and we were happy to receive many replies! Thank you so much! Some of those replies spoke about prayer, and one testimony from an elderly sister made an especially deep impression on me:

I think the horarium of most of our houses has scheduled a period of silent prayer after vigils and vespers. . . . Liturgy is our central prayer; lectio, the rosary, . . . are always encouraged; prayer in general is greatly respected in my community, but I have heard nothing about contemplative prayer in my years here.

In my opinion, this exposes the current crisis in our monastic life quite precisely: we lack proper meaningful formation in silent personal prayer. In many visitation cards I hear the complaint that not all brothers and sisters are faithful to the periods of silent prayer (after vigils and vespers). Are our communities “houses of prayer”? Isn’t the vocation to unceasing prayer the fundamental desire which brought us to the monastery? We wanted to dedicate our lives to prayer, but how true are the following words of Hans Urs von Balthasar:

Most Christians are convinced that prayer is more than the outward performance of an obligation, in which we tell God things he already knows. It is more than a kind of daily waiting attendance on the exalted Sovereign who receives his subjects’ homage morning and evening. And although many Christians experience in pain and regret that their prayers get no further than this lowly stage, they are sure, nonetheless, that there should be more to it. In this field there lies a hidden treasure, if only I could find it and dig it up. This seed has the power to become a mighty tree bearing blossoms and fruit, if only I would plant and tend it. This hard and distasteful duty would yield the freest and most blessed kind of life, if only I could open and surrender myself to it. Christians know this, or at least they have an obscure intimation of it based on prior experiences of one kind or another, but they have never dared to follow these beckoning paths and enter the land of promise. The birds of the air have eaten up the sown word, the thorns of everyday life have choked it; all that remains is a vague regret in the soul. And if, at particular times throughout life, they feel an urgent need for a relationship with God which is diOerent from the incessant repetition of set prayers, they feel clumsy and lacking in ability, as if they had to speak a language without having mastered its grammar. Instead of fluent conversation they can only manage a few, halting, scraps of the heavenly idiom. Like a stranger in a foreign land, unacquainted with the language, they almost become inarticulate children again, wanting to say something but unable to do so.

This is a long but rich citation which we should read over and over again, and in which we can certainly replace the word “Christians” with “monks and nuns.” Have we received proper formation for prayer? Are we giving proper formation for prayer? Have we learned the language of this ongoing conversation with God? Are we ourselves guided on that path of unceasing prayer? Or has all of this come to a halt due to everyday worries, disappointments and frustration? If we no longer speak the language of prayer, how can our communities be a “school of hope” for others?

Some months ago, I received a letter from a young man who was very disappointed in our monasteries. He had knocked on the doors of several of them, seeking out our monks and nuns because he wanted to learn how to pray. Maybe he was just knocking on the doors of the wrong monasteries, but the brothers and sisters he encountered could not help him; they had neither the language nor the interest. One monastery invited him to the Divine Ocice, but the young man was not looking for that; he wanted intimate personal conversation with God. One monastery gave him the Lord’s Prayer, but he wanted more than just “incessantly repeated formulas.” Another monastery recommended that he go and ask the Carmelites. What a missed opportunity! But also, what a worry when we can no longer speak and transmit the language of prayer, when we can no longer show others how to pray!

With this letter, I invite you to look at your personal prayer in which we are “constantly cultivating mindfulness of God” (C. 20), at this personal prayer which is the culmination of the Divine Ocice and our lectio divina, “a source of prayer and a school of contemplation, where the monk and nun speak heart to heart with God.” (C. 21) What C. 45.2 says is true: “Solitude, continual prayer, humble work, voluntary poverty, celibate chastity, and obedience are not human skills, and cannot be learned from human beings.” But we should not forget the rest of this Constitution: “Nevertheless, the teaching of the abbot/abbess, the experience and wisdom of the seniors, and the constant help and example of the community are of great value to the brothers/sisters as they pass through the diOerent situations and changes of the spiritual journey.”

I will give you three words to help in your consideration: Silence, Simplicity and Solidarity. Hopefully these three words will help you rediscover (if necessary), renew and deepen your personal prayer and find a language to transmit this central element of our Cistercian charism to others.

PRAYER AND SILENCE

When the General Chapter of 1969 considered how the Order should respond to the challenges of Vatican II, two documents were drafted that later became the basis for our renewed Constitutions and Statutes: the Declaration on Cistercian Life, and the Statute on Unity and Pluralism. Both documents insist on the inseparable link between silence and prayer in our monastic life. SUP no. 5 states, “The monk, who is tending to a life of continual prayer, needs a fixed amount of prayer each day”; and no. 6 adds, “This search for a life of prayer should be lived in an atmosphere of recollection and silence for which all are responsible. In particular, the great silence at night and the silence in the regular places will be maintained.” The Declaration on Cistercian Life confirms this connection when it says “an atmosphere of silence and separation from the world” that “fosters and expresses its openness to God in contemplation . . . treasuring, as Mary did, all these things, pondering them in her heart.”

Constitution 24 on silence says:

Silence is counted among the principal monastic values of the Order. It assures solitude for the monk in community. It fosters mindfulness of God and fraternal communion. It opens the mind to the inspirations of the Holy Spirit and favors attentiveness of heart and solitary prayer to God. Therefore, at all times but especially during the hours of night, the brothers are to be zealous for silence, which is the guardian both of speech and of thought.

Silence fosters, opens and favors our solitary, silent prayer with God.

But what exactly is this silence? In Spe Salvi, his encyclical on hope, Pope Benedict XVI states: “It is an active hope also in the sense that we keep the world open to God.” Silence keeps the world open to God! Thomas Merton tells us:

The monastic vocation is by its very nature a call to the wilderness, because it is a call to live in hope. The monk carries on the long tradition of waiting and hoping, the long Advent of the patriarchs and prophets: an Advent which prolongs our expectation even though the Savior has come. . . . The monk leaves the world, . . . descending by his prayer into the empty spaces of his own spirit, he waits for the fulfillment of the divine promises: “The land that was desolate and impassable shall be glad, and the wilderness shall rejoice and shall flourish like the lily. (Is. 35:1). . . Hope, too, is hidden in silence.

Prayer needs silence, and this silence in turn fosters, opens and favors prayer. This is how hope is born into the world, a world trapped in a life without hope, a world which also includes the hearts of monks and nuns. Hope lies hidden in silence and prayer; in silence and prayer, hope cries out!

PRAYER AND SIMPLICITY

Silence. “It is an active hope also in the sense that we keep the world open to God.” These words of Pope Benedict XVI show us that prayer and silence are essentially linked if prayer is to be a school of hope. Dom André Louf OCSO (1929-2010) adds:

Another characteristic of this interior prayer in the Holy Spirit is its need for simplicity. After a time, prayer becomes frugal. The many words of the initial stage diminish into silence and die away. The man of prayer will restrict himself to a single formula, sometimes to a single word, or simply to the Name.

Ecclesiastes 5:1 says, “Do not be quick with your mouth, do not be hasty in your heart to utter anything before God. God is in heaven and you are on earth, so let your words be few.” In Matthew 6:7, Jesus says, “And when you pray, do not keep on babbling like pagans, for they think they will be heard because of their many words.” Prayer with Jesus is simple. Very few words need to be spoken.

St. Benedict has this same attitude of simplicity when he speaks of prayer: “Prayer, therefore, must be short and pure, unless one feels impelled by a desire, prompted by God’s grace, to go on with it. But when praying in community, the prayer should be very short, and as soon as the superior gives the sign, all should rise together.” (RB 20:4-5) With St. Benedict, this short and pure prayer had its origin in the prayer of the desert fathers who alternated or accompanied their manual labor with short and simple prayer formulas.

This telling quote is from the famous ladder of St. John Climacus:

Let your prayer be simple and without many words: one word was enough to procure forgiveness for the tax collector and the prodigal son. . . . Don’t go chasing after this or that formula for the words of your prayer. A child’s simple and monotonous stuttering is enough to convince its father. Don’t be long- winded. You will distract your mind if you go searching for words. One word from the tax collector moved God to compassion. A single word of faith saved the good thief. Lengthy prayers build up all sorts of images in the mind and distract it, whereas a single word can bring the mind to a state of recollection. If you feel that you are inwardly calmed and contented by uttering a single word, then stay with that word, for then your angel is praying with you.

The monk’s simple prayer always brings him back to the liturgy, to his lectio divina or simply to the name of Jesus. Dom André Louf writes:

In addition to the cry of the tax collector, the Name of Jesus itself plays an important part in the Jesus prayer. Actually, it can become even simpler, for the Jesus prayer may well be reduced to the simple invocation of Jesus’ Name. The Name of Jesus is charged with invisible and unsuspected power: strength in temptation, and consolation where there is a yearning for love. “The manifold repetition of this Name,” the blessed Aelred writes to his hermitess sister, “pierces our heart from within.”

Dom André Louf has a beautiful description of this prayer: “this simple Response, precisely because it is simple, can be uttered in us only by the Spirit, which takes us completely in tow.” May our prayer be a single, simple Response!

PRAYER AND SOLIDARITY

The hope that emerges from the school of prayer is rooted in silence and simplicity, but grows and extends to all creation, which brings solidarity to our attention. When asked why a Cistercian monastery was present in an all-Islamic environment, Blessed Christian de Chergé replied: “to be prayers among prayers.” With these words, he shows how this central word of our charism takes on its own meaning in a context entirely dicerent from that of our Holy Founders, not as a challenge but as an appeal.

This response from the blessed brothers of Tibhirine may still be an appeal for many of us, but for those who live in an increasingly secularized world, or even in a world that thinks it can live without God, our charism demands a new language to express itself and to become attractive again.

That world needs our charism of unceasing prayer to keep it open to God, open to that other Reality in whom we are loved and who is worth loving. The most visible way in which we, as monastic communities, keep this world open to God through our prayer is in the public celebration of the liturgy. But are not many people touched by the silent, intimate prayer of a monk or nun?

Heureux ceux qui prient is a collection of thoughts on prayer from the brothers of

Tibhirine. It begins with a long, impressive quote from a young Muslim who had visited

the monastery for several days:

To all my brothers in faith, after spending three days of silence in this holy place, lost in nature, where my brothers are called “monks,” you who have renounced everything in order to possess everything, you who have separated yourselves from everything in order to be united with everyone, you who have freed yourselves from all selfishness and all restlessness in order to surrender to the Sovereign Spirit of God, and this task is your ministry for an entire lifetime. . . .

I, who have not yet discovered the essential path, have just been taught by you how to sacrifice my life to encounter God, with no panic in my heart; I have been taught by you how to seek to possess God in my own actions. . . .

My father, who is a Muslim priest and very attached to Islam, used to tell me that all Christians go to hell. On my return, I told him that, according to our own judgement, it’s not easy to cross the threshold of hell, nor is it easy to cross the threshold of paradise, but my brothers at Tibhirine spend their entire lives being who they should be, rather than doing what they should do, and it is these brothers, suspended between heaven and earth, who are keeping the gate of communication open. I will tell him that a “monk” is a true Light that enlightens every man who comes into this world. . . . This monastery is a special school of love, and indeed I have found no other motive here than Love, for God is Love. . . .

Your homes, your souls, your lives are occupied by God who has a right to everything; he takes your hours, but he also fills them, and tomorrow you will be well rewarded. . . . Happy is the one who allows God to dwell in his heart.

“Keeping the gate of communication open,” or in other words, keeping the world open to God. “Happy is the one who lets God dwell in his heart.” This is not a work that relies on our own strength, but a work that we do in silence and simplicity. This is the reason why the hidden aspect of our prayer and our monastic life is of great importance. “By fidelity to their monastic way of life, which has its own hidden mode of apostolic fruitfulness, monks/nuns perform a service for God’s people and the whole human race” (Cst. 3.4).

This hidden apostolic fruitfulness has its origins in silent, simple prayer which, according to Brother Christophe Lebreton, is “that double movement of the heart which invites us to stay (with, near…), and to leave. Rest and exodus.”

Fr. Thomas Keating OCSO, another great master of contemplative prayer, speaks of “the transforming union” of prayer in this same context. He sees the first fruit of the hidden apostolic fruitfulness of prayer as “a way of being in the world that enables us to live daily life with the invincible conviction of continuous union with God. It is a new way of being in the world, a way of transcending everything in the world without leaving it.” The second fruit will be the final union with God after our death, when we take all of God’s creation with us into that final union.

For Keating, the solidarity born of prayer is

. . . a tremendous concern for everything that is, but without the emotional involvement characteristic of the false self. We are free to devote ourselves to the needs of others without becoming unduly absorbed in their emotional pain. We are present to people at the deepest level and perceive the presence of anything from them. We simply have the divine life as sheer gift and offer it to anyone who wants it. The risen life of Christ through the gifts of his Spirit can then suggest what is to be done or not done in incredible detail. This state of consciousness is not passing, but a permanent awareness that spontaneously envelops the whole of life.

As a result, a new dimension of the whole of reality emerges: in Christ, we are connected to all and to everything; we know an inner solidarity that will express itself in concrete actions. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

2565 Prayer is Christian insofar as it is communion with Christ and extends throughout the Church, which is his Body. Its dimensions are those of Christ’s love (Cf. Eph 3:18-21).

2718 Contemplative prayer is a union with the prayer of Christ insofar as it makes us participate in his mystery. The mystery of Christ is celebrated by the Church in the Eucharist, and the Holy Spirit makes it come alive in contemplative prayer so that our charity will manifest it in our acts.

2719 Contemplative prayer is a communion of love bearing Life for the

multitude . . .

If we lose this hidden apostolic fruitfulness of our contemplative prayer, if we lose our co-responsibility for mission, then

…interiority can turn into pietism (mawkish, sentimental devotion), quietism (inert expectation of mystical movements deemed necessary for salvation), romantic reverie, or even outrageous psychologism or superstition. Feeling and sensation become the criteria for spiritual experience.

In conclusion

Brothers and sisters, I hope these modest incentives can be of help to all of you, both as communities and as individuals, as you reflect explicitly on your personal, unceasing, silent prayer which lies at the heart of our Cistercian charism: listen to each other’s experiences of personal prayer as you come together in spiritual conversation; perhaps choose a book on prayer for your Lenten reading during this coming season of Lent; or just start over again with personal, silent prayer. The Church as well as the world expect us to use this gift which we have received from God today, to make God present in our world. Our co-responsibility for the mission of the Church is really to become the praying heart of his mystical body.

God has given us this gift of prayer! Do not doubt it! Remember the beautiful text we have received from St. Bernard:

. . . this is what I say: that even though a soul is so condemned and so desperate, nevertheless it is my teaching that such a soul can find within itself not only a source of relief in the hope of pardon, so that it may hopefully seek mercy, but also a source of boldness, so that it may desire marriage with the Word, not fearing to enter into a treaty of friendship with God, nor being timid about taking up the yoke of love from him who is the King of angels.

May our communities be schools of hope through our assiduous prayer. Let us not forget that hope has often unexpectedly changed the course of history. Our prayer can do the same! Let us persevere in that quiet, simple prayer that unites us with all creation.

May Our Lady of Silence be our example, as our Constitutions tell us: “May the Blessed Virgin Mary, who was taken up into heaven, the life and sweetness and hope of all earthly pilgrims, never be far from their hearts.” (Cst. 22)

Look at Christ with Mary’s eyes, with her heart, with her memory. Often our eyes are ‘cloudy’: we must put on Mary’s ‘glasses’. Try to believe and believe to try!

Prayer. Try to hope and hope to try!

Br. Bernardus Peeters OCSO

Abbot General

Rome, 26 January 2025

Solemnity of our Holy Founders